Are you the kind of person who knows every component of a modern computer or smartphone, or do you just accept that your devices work "by magic" and just worry about using them? What about cars? Refrigerators? Cellular networks? With the ever expanding scope of technology, the challenge of understanding how it all works is a major dilemma for today's society.

So how does the Internet work?

...

Got an answer? If you're going to be creating content for the web, it's a good idea to have at least a basic grasp of what's happening behind the scenes.

The Internet (derived from "internetwork") is a global network of networks that facilitates the transfer of data. The World Wide Web (WWW) is a public information space that relies on the infrastructure of the Internet to share web content. This means that while most people use the terms interchangeably, the Internet and the Web are not the same thing. Think of the Web as a portion of content that is transferred over the infrastructure of the Internet; email, file-sharing, and mobile apps also transfer data through the Internet , but the do not constitute parts of the Web (e.g. webpages).

In 2016 the Associated Press and New York Times updated their style guides to spell Internet with a lowercase "i" as more and more people refer to it colloquially and not as a proper noun—but I'm a traditionalist.

HTTP & HTML

Like most computer programs, webpages can be completely reduced to text, which is how content is transferred online. Web browsers like Chrome, Firefox, and Safari render those text files as webpages to create the visually compelling experience you're used to seeing online. If you want to see what the raw text version of a web page looks like, try to following on any website:

Right-click on an empty portion of the web page (not on text or images), and select View Page Source (Chrome or Firefox) or Show Page Source (Safari).

Go ahead and try it.

...

Back now? Okay. In take that text and render it consistently on any device, anywhere in the world, webpages are build and shared within a set framework called HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP). HyperText refers to interconnected content that can be linked together via hyperlinks, but let's get too technical.

The actual content that is transferred via HTTP over the Internet are typically text files written in HyperText Markup Language (HTML), although some websites use a different coding language (PHP or Java) to create HTML files every time a user other coding languages can be involved in the creation of those HTML files (for example Wordpress uses a language called PHP to generate HTML files, but that's beyond the scope of this article).

Web browsers can read other types of files too, for example, you can open a JPEG in your web browser—either right-click the file and choose "Open with" or drag it onto the icon in the doc if you're on a Mac.

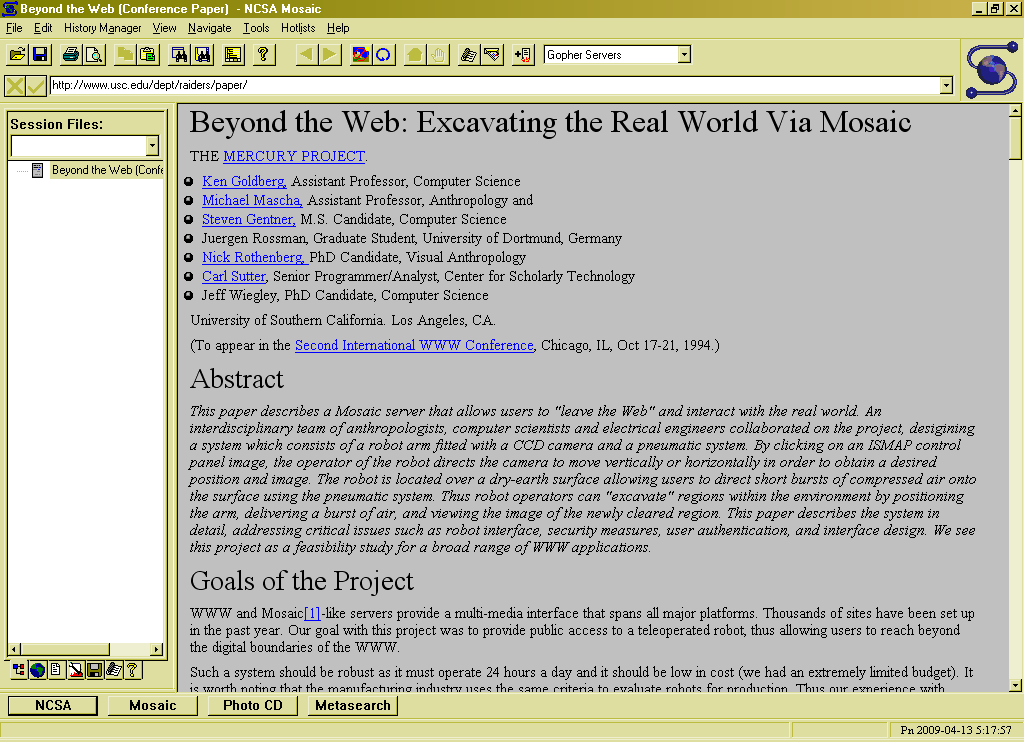

You should try this too. If you need an image file, you can download this image of the first web browser with a graphical interface (called Mosaic, from 1993). Also—does Mosaic look similar or different from your current web browser? What are some of the design details that have stuck around for 20+ years?

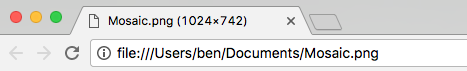

Once you've opened a JPEG or PNG in your web browser, take a look at the URL bar at the top of the screen.

Instead of the traditional "http://www..." you should see something like the following:

This is the path for whatever file you opened. The slashes denoted folders, meaning that my file "Mosaic.png" is located in my Documents folder, within my user folder, within a folder called "Users", which is within the root level folder of my computer.

Now if you haven't done any sort of coding before, this might blow your mind, but any URL you type into your web browser is the same sort of file path—except the files you're opening are usually HTML files (e.g. "http://website.com/something.html"\) and not JPEG's. So when you go to http://www.worldcampus.psu.edu/about-us/mission you're accessing a file called "mission" within a folder called "about-us." Sometimes the file extension will be hidden by the browser, but oftentimes you will see URL's ending in ".html"

Unlike the image you opened earlier, webpages are not saved on your local computer; they're saved on a computer somewhere else on the planet. These computers are called servers, and they're built specifically to host files and make them accessible over the Internet. Here's a comically boring server center from the show Silicon Valley:

![]()

We'll get into the details of how to upload files to and from a remote server soon, but for now just appreciate the fact that every page you visit online is a portal into a computer somewhere else in the world.

It's entirely possible to create HTML files on your local computer and view them in a web browser.

In fact, that's what we're going to do in this lesson.